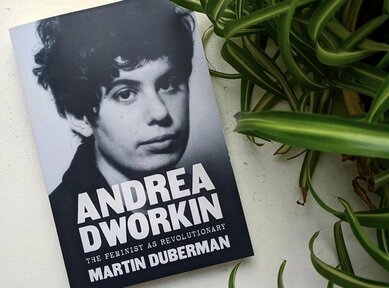

On Andrea Dworkin - Sam Huber in NYRB:

‘Once, when explaining—that is to say, justifying—my interest in Andrea Dworkin to a receptive acquaintance, I began by insisting on Dworkin’s literariness. It seemed a less perilous way to recuperate her in their esteem than her politics. Literariness can be curious, ahistorical, a supple cover for all kinds of quirks, under which the unseemly or obsolete assumes the less threatening guise of idiosyncrasy. Politics must clear a different hurdle; we tend to demand they hold up to scrutiny in the present tense. Dworkin’s, I conceded, don’t, or at least not as we’ve inherited them. But she could write. She could write about books, even! My favorite Dworkin essay—I continued, courting my friend’s skepticism—is a piece of literary criticism about Wuthering Heights. She was a brilliant close reader. Dworkin, the polemicist? Dworkin, metonym for an outmoded Second Wave stridency? Any such conversation owes some credit to Johanna Fateman, who first began making Dworkin available to contemporary feminist thought with an essay in the 2014 anthology Icon and later with Last Days at Hot Slit, a 2019 selection of Dworkin’s writings she coedited with Amy Scholder. The raft of coverage about Last Days made me realize that by easing into Dworkin through literature I was implicitly apologizing for her, not critiquing so much as denying the politics that formed the core of her life’s work. She wanted badly to be a writer, but she wanted even more to end male supremacy and its attendant order of sexual division—in all its forms, but especially as it manifested in rape and circulated as pornography.’

(…)

‘Like many women’s liberationists, Dworkin came to radical politics by way of the antiwar movement, the New Left, and Black Power. The film lingers on these influences. Significant time is given to Dworkin’s impassioned descriptions of Frantz Fanon and Huey Newton, from whom she learned not just methods of analysis but modes of address—especially a colloquial, swaggering style, a way of playing rhetorical offense, which she spent her career honing. Parallel instruction came from the arts. She admired Bach for his “repetition, variation, risk, originality, and commitment…I wanted to do that with writing.” The male gods of the countercultural pantheon—Lawrence, Genet, Miller, Baldwin—were hers, too. Allen Ginsberg, whom she met at a 1967 reading at St. Mark’s Church, encouraged her as a poet.’

(…)

‘When she moved to Europe in 1968, Amsterdam initially offered a countercultural swirl of art, protest, and sex. (“I liked revolution as foreplay.”) Her marriage to a man from this scene, Iwan de Bruin, abruptly turned nightmarish. He beat her often and with impunity; neighbors, doctors, and Dworkin’s own parents witnessed or overheard his abuse but declined to intervene. Again she came up against the limits of language: she tried to ask for help but “my words didn’t seem to mean anything.”’

(…)

‘But Dworkin rejected the patriarchal equation of anatomy with identity, and she warned feminists against reiterating it in new terms. She was desperate to protect women but had no interest in defending the category “woman.” For what it’s worth, I’ve always found 1970s feminist writing about androgyny—by Dworkin, Carolyn Heilbrun, Toni Cade Bambara, and others—enabling of rather than threatening to a trans-affirming political vision, whatever those thinkers may otherwise have said or failed to say about trans people. In Woman Hating, Dworkin imagined a “road to freedom open to women, men, and that emerging majority, the rest of us.”’

(…)

‘Dworkin’s anti-pornography campaign was as controversial for its strategy as for its intellectual underpinnings. With the legal scholar Catharine MacKinnon, she attempted to pass a series of city-level ordinances framing pornography as a civil rights issue for women. These ordinances would have given anyone who felt they had been harmed by pornography grounds on which to sue pornographers for damages; they would not have criminalized pornography or authorized direct state censorship. This distinction, though vitally important to Dworkin and MacKinnon, did little to reassure feminists who feared that any effort to enlist the law in the regulation of sexually explicit media would only hurt women and queers. Ellen Willis, one of Dworkin’s most rigorous feminist detractors, warned that anti-porn activism posed a threat both to the First Amendment and to the integrity of the women’s movement, widening its “good girl–bad girl split.”

Wisely, My Name Is Andrea incorporates more voices into its second half than its first, sampling the heated dissensus around pornography in the 1980s and 1990s. MacKinnon and Dworkin explain their ordinance on a TV news segment; another newscaster announces its veto by the Minneapolis mayor. A clip from a televised interview with Carole Vance, organizer of the notoriously contentious 1982 Barnard Conference on Sexuality, stands in for a larger chorus of feminist opposition:

I think we use this word “pornography” at our own peril. We each use it believing we mean the same thing as the other person; we almost never do. Pornography includes sex-education material; it includes gay and lesbian literature; it would include a great deal of recent feminist art and literature as well.

It’s an admirably tight and cogent soundbite, but too brief—and perhaps too diplomatic—to reflect just how caustic these disputes became.’

(…)

‘Dworkin was often dismissed as analytically crude and rhetorically divisive, but her books have always been most useful to me for their insistence that patriarchy itself imposes crudeness and division. It herds vast human capacity into narrow pens of the permissible, by seduction or force. We call those pens gender, and they keep us from each other.’

Read the article here.

Andrea Dworking is a very good reader and also for that reason a good and interesting writer. It’s not always necessary to agree with Freud or Marx – just to name two thinkers who have influenced our culture immensely -the same can be said about Dworkin, even though her influence might have been slightly less overwhelming than Freud’s.

Her essay on Tolstoy impressed me and it you want to read Tolstoy again.

And ye, patriarchy is as disgusting as fascism.

But where civilization is we will find ‘vast human capacity [ that has been herded] into narrow pens of the permissible’, but perhaps the distinction between patriarchy and civilization is let’ say invisible.

In that case, we should all be waiting for a new civilization. Or we might try to be the midwife of the new civilization with violent and less violent means.

As an admirer of Beckett I’d like to wait patiently.