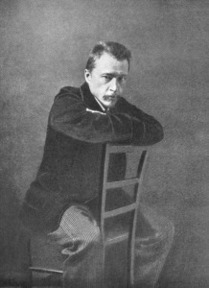

On Lieder – Ian Pace in LRB:

“It wouldn’t be difficult to construct a history of 19th-century Germanic music that left out the name of Hugo Wolf entirely. Part of the reason is the mixed reputation of Lieder, or solo song. Accounts of Beethoven afford a central place to his symphonies, concertos, string quartets and sonatas, but the status of his songs, with the possible exception of the cycle An die ferne Geliebte, is more equivocal. Schubert’s song cycles Die schöne Müllerin and Winterreise are recognised as the peaks of his output, alongside a handful of other Lieder, but these amount to only a fraction of the more than six hundred songs that he completed. The same goes for Schumann’s Dichterliebeand Frauenliebe und Leben. Brahms’s reputation is secure thanks to his symphonies, concertos, much of the chamber music, and some of the piano works. But very few of his 196 songs for solo voice and piano have achieved lasting popularity or a regular place in concert programmes. Of later Lieder composers, Mahler is admired for his symphonies and Richard Strauss for his symphonic poems and operas.”

(…)

“In 1879, Wolf met with Brahms, whom he had previously admired. The encounter didn’t go well. Wolf took offence when Brahms recommended a rather conservative teacher, Gustav Nottebohm, whom he couldn’t afford and who anyhow wouldn’t have suited his temperamental resistance to authority. Following the meeting, Wolf became a staunch opponent of Brahms’s work. From 1884 to 1887, he wrote for the Wiener Salonblatt, in vehement opposition to Hanslick at the Neue Freie Presse. Wolf’s passionate advocacy of Wagner came to be matched by attacks on Brahms as vicious as Hanslick’s on Bruckner. Wolf asked why ‘these glue pots, these obscenely stale symphonies of Brahms, false and perverted to the bottom of their very soul, are hailed as wonders of the world,’ finding ‘more intelligence and sensitivity in a single cymbal crash in a work by Liszt’. Of Brahms’s First Piano Concerto, he wrote: ‘There blows a draught so cold, so chilly damp, so foggy, that one’s heart can freeze, one’s breath be taken away. One could catch cold from it.’ He also complained that critics seemed to demand that performers play Brahms if they hoped to be reviewed.”

(…)

“Suffering from inflammation of the throat, which may have been a symptom of syphilis, Wolf fell into another depression, and wrote almost nothing between 1892 and 1894. When he resurfaced, he set his attention to the composition of Der Corregidor, which was performed in Mannheim in 1896. Then he went back to the Italienisches Liederbuch, which he completed in another furious burst of activity in March and April 1896, by which point he had achieved some financial security, in part through the ministrations of friends.

Wolf composed three settings of sonnets by Michelangelo in 1897, and began work on another opera, Manuel Venegas, which he never completed. His mental vicissitudes, together with further symptoms of syphilis, became increasingly acute, and later that year he was taken unwillingly to an asylum. Despite some respite in 1898, he voluntarily returned to another asylum the following year after an attempt to drown himself. He remained there until his death in 1903, visited regularly by his mistress, Melanie Köchert. She took her own life in 1906.”

(…)

“Stokes quotes extensively from Wolf’s letters. Many are unremarkable, but there are exceptions, such as the letter he sent to Kauffmann in March 1894 after reading Eichendorff’s novella Dürande Castle:

Eichendorff’s characteristic chiaroscuro atmosphere is simply not compatible with the bright lights of the stage. I would call his stories literary landscapes, in which all the delineated characters play a merely secondary role, resembling what painters call staffage. The reverse is true of the theatre: the decor is staffage & the characters must be placed in the foreground with the greatest possible clarity. Consider now a typical Eichendorff character. There’s hardly anything but his costume & a bit of make-up. Not a trace of portrayal or psychological perspective. Only vague shadowy silhouettes, without faces or personality; they suddenly appear like dreamy ghosts – no one knows from where – then vanish, no one knows where to. They drift along like clouds in the sky or, to use an Eichendorff image, like silent dreams, assuming now this form, now that. That’s all very well & highly poetic & agreeable for the imagination – but of no use at all in the theatre.

This explains much about Wolf’s approach in such Eichendorff settings as ‘Der Soldat I’ or ‘Nachtzauber’, in which bland vocal lines, sometimes within a limited tessitura, are transformed by the role of the piano.’

Read the article here.

In the category deadly comments ‘One could catch cold from it’ stands out.

The life of Hugo Wolf is also very much suitable for a novella.

According to this his article his Lieder remain an open question, but life it not always fair and neither is history.