On anarchism – Greg Afinogenov in LRB:

“In exile, Kropotkin drew on both his scientific and political interests to create the theoretical foundations of modern anarchism. His comrades in Russia, who were known as narodniki, or populists, shared many of his views but not all. Inspired by their liberation of Kropotkin and other daring feats, some of them embarked on a campaign of terrorism that culminated in the assassination of Alexander II in 1881. They demanded constitutional rights and an elected government, both of which Kropotkin repudiated. Yet connections were maintained: when Kropotkin returned to Russia, the Provisional Government – then led by Alexander Kerensky of the neo-populist Socialist Revolutionary Party – offered him a ministerial portfolio of his choice. He refused, saying that he thought being a cobbler was a more honourable trade, but he continued to support Kerensky’s doomed government and its commitment to staying in the First World War.”

(…)

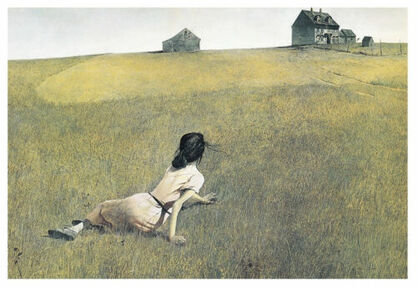

“By the 19th century, however, educated elites all over Europe were drawn, whether by poetry, paintings or music, towards a romantic notion of the rural poor. The beginnings of capitalist industrialisation and the effects of the Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars had made rustic virtues more attractive. Johann Gottfried von Herder linked this shift to a rejection of Enlightenment universalism. Rather than seeing all societies as occupying different rungs on a ladder of ‘politeness’ and modernity, he and his followers argued that national – and ultimately racial – particularities could never be fully ironed out. These distinctions were most visible not in the lives of the upper classes, which had become more and more homogeneous, but in the apparently primordial culture of the common folk.

The Russian word narod is similar to the German Volk, but while Volkishness became associated with conservative nationalism, narodnichestvo belonged mostly to the left. The post-Petrine state remained firmly committed to the Westernisation that had created it. Even during the reign of Nicholas I (1825-55) – an arch-counterrevolutionary – the embrace of narodnost (sometimes translated as ‘nationality’ but meaning something like ‘being of the people’) remained relatively superficial. It was the Slavophiles, a group of Herder-inspired intellectuals based in Moscow, who first developed narodnost into a potentially subversive doctrine. While they rejected revolution or political reform, they believed that the communitarian, pious, localist beliefs they attributed to the Russian peasantry constituted a kind of spiritual alternative to the power-grasping of the imperial bureaucracy and its courtiers.”

(…)

“The utility of this half-imaginary peasant commune for adherents of an anti-Western, traditionalist persuasion was obvious, but it proved even more influential on the political left. An early enthusiast was Alexander Herzen, whose rather mild anti-regime activities led first to a state-imposed exile from the centres of imperial power in St Petersburg and Moscow and then to a self-imposed flight to the West. Herzen initially found inspiration in the French Revolution, but the suffocating bourgeois capitalism that had triumphed across Europe and culminated in the failed revolution of 1848 led him to seek alternatives elsewhere. Before his emigration he had opposed the Slavophiles; now he believed they were on the right track: the future of socialism meant merging the economic form of the Russian peasant commune with the radical ideals of the European left.

Herzen, like Kropotkin, belonged to a distinctive social category: Russian nobles who were consumed by guilt and anger about the role they were destined to fill. As Herzen put it, the recipient of a high-quality humanistic education would eventually have to ask himself, ‘Is it absolutely essential to enter into the service? Is it really a good thing to be a landowner?’ For those who could not confidently answer yes, the way out was to sink into dissipation – or to turn against the system that created them. A revolutionary movement defined by such people is, of course, inherently limited because of its inability to mobilise the masses whose discontent it claims to represent.”

(…)

“Kropotkin had been helping to plan a project which went ahead that summer: the ‘going to the people’ movement in which thousands of populists from St Petersburg fanned out across the empire, mixing with the peasantry to agitate for a revolutionary uprising. The peasants were not, on the whole, prepared to go along with this, and many populists returned deflated; others were betrayed to the police, dragged back to St Petersburg in chains and put on trial for subversive agitation. The outcome was ambiguous at best. While ‘going to the people’ showed many left-wing radicals that the Russian peasantry wasn’t the revolutionary mass they had imagined it to be, the unexpected support given by liberals in the imperial capital to prisoners of conscience – including the populist Vera Zasulich, who had tried to assassinate the brutal governor of St Petersburg – suggested another means of achieving their goal.”

(…)

“They hoped to spark a broader revolt with dramatic acts of terror plotted and executed in secret – such as the massive bombing they carried out at the Winter Palace in 1880, which narrowly missed the tsar. But when they finally succeeded in killing him a year later, the only spontaneous uprising that took place was a pogrom against the empire’s Jewish population. The secret police swiftly rounded up and executed the terrorists, and the populist movement entered a period of decline.” (…)

‘The last century of human history has dampened the appeal of Kropotkin’s optimism. The anarchist trade unions and co-operative movements that inspired him in his own time have lost much of their significance, and it would be hard for an outside observer to dispute Eric Hobsbawm’s claim that ‘the history of anarchism, almost alone among modern social movements, is one of unrelieved failure.’ But if anarchism was a failure, Russian populism fared even worse. After the collapse of the terrorist strategy a decade of tactical retreat followed in which some of the populists abandoned their revolutionary commitments while the folkish aspects of their worldview were partially co-opted by right-wing rivals. The radical heirs of Land and Freedom began to lose ground to the Russian version of social democracy. The work of Karl Kautsky – Marxism’s Saint Paul – inspired a new generation of revolutionaries, including former populists such as Zasulich. Against the populist emphasis on agrarian revolt, social democrats tried to pursue the merger of organised socialism and the underground (but growing) labour movement. The Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP) as well as other groups, in particular the Jewish Bund, targeted Russia’s industrial worker population and forged a new alliance between educated intellectuals and militant proletarians in underground reading groups and organising committees. Social democracy succeeded in rallying masses that the populists could never reach. In the Revolution of 1905, millions of striking workers seized power at the local level. They formed soviets: federated direct-democratic governing bodies in the best anarchist tradition. That revolution was swiftly defeated, but the precedent it established was essential to what came next.”

(…)

“Lenin admired Kropotkin nonetheless. As his secret police hounded down the last remnants of Russian populism, he ensured that Kropotkin could live out his declining years in comfort at his dacha outside Moscow. When Kropotkin died in February 1921, dozens of anarchists were released from Moscow’s prisons to attend the lavish funeral and all the leading party newspapers carried laudatory announcements. A few weeks later, there was an uprising at the naval stronghold of Kronstadt, in which anarchists and left SRs played a leading role. The Bolsheviks wiped out every cell they could find. Anarchism and populism had few enemies more bitter than the Soviet brand of communism; this was because the Bolsheviks saw themselves as both continuing and overcoming the revolutionary tradition these approaches represented. But thanks to the Soviet government, streets, squares, towns and metro stations all over Russia still bear Kropotkin’s name”

Read the article here.

The foremen of many revolutionary moment, the sons and daughters of the upper class haunted by guilt, anger and boredom.

About ten years ago, when I was in Greece to write about the Greek crisis, I met quite a few anarchists. There was something tragic about them, they were firm believers in their ideology, but they seemed to realize that they were doomed to operate in the periphery of the periphery. Perhaps this is what faith is, knowing that you are doomed but you continue anyway.

You become a believer or a fanatic, or both.

The adoration of ‘rustic virtues,’ the rejection of everything that can be labeled modernity continue.

The longing for authenticity, the longing to find a pure place filled with pure people, people who are not yet corrupted by any kind of pragmatism, it’s all still there. And violence is never far away.

The rejection of modernity has almost always been a violent affair.