A friend sent me this review by Dalia Sofer on Jennifer Hofmann’s debut novel ‘The Standardization of Demoralization Procedures”. A great title by the way:

‘Yet within his impassivity lives one obsession: Lara, the waitress at the corner cafe who used to serve him cheese toast and milk coffee daily, and to whom he once confessed all of his deeds and misdeeds — including his involvement in the conviction of Johannes Held, a physicist whom he simultaneously befriended and betrayed for a confession. The morning after his own unburdening, Lara mysteriously disappeared.

The young woman’s absence is but one of many vanishings in the novel. Also gone are several youths: Held, who once researched quantum entanglement in the Arizona desert alongside American scientists who were conducting experiments on teleportation; Mexican children in that same desert; and now Zeiger himself, who’s slowly slipping from his own life. Encompassing these vanishings is a more absolute void: the absence of memory, confiscated by the state and replaced by ideology.

Of his childhood, Zeiger retains little. His father served in the war and was later sent to a Soviet prison camp; his mother read him “Struwwelpeter” stories (19th-century cautionary tales for children by Heinrich Hoffmann) and once took him to see the preserved corpse of Knight Kahlbutz in the catacombs of Kampehl. His first conscious moment arrived when one winter morning during the war, his mother took him to Lake Müggelsee and threw him into the icy water, leaving him to sink underwater before retrieving him. “Men don’t catch death,” she told him afterward, believing she had made him invincible. When years later, in 1954, his father’s ashes were sent from the prison camp in a small box, his mother killed herself with her Walther service gun. Following her death, whatever was left behind — her collection of Meissen porcelain, her Solingen silver, some jewelry, her Walther and his father’s wartime pin of the “grinning skull” (the Totenkopf, the insignia of the SS) — was confiscated by the state. A final act of liquidation, not only of property, but also of memory.’

(…)

‘This is important, and perhaps not stressed enough in the novel. Designating Hitler as a legacy of West Germany was among the tenets of the German Democratic Republic, which crafted a historiography of itself as a longtime opponent and victim of fascism. Wartime guilt, and all its associated convulsions, were therefore assigned to those living on the western side of the wall. While this may not answer “the whys and the hows” Zeiger seeks, it does serve as a reminder that even the negation of history — misguided and doomed to fail — arises from human frailty, our inability to reckon with ourselves.’

(…)

‘But the capsizing, which reaches a pinnacle at the novel’s clever, dramatic end — a testament to the manual’s perfect triumph — may nonetheless be too neat a resolution, historically. East Germany imploded, but neither its creation nor its demise was as vacuous as the novel suggests. Throughout the book Zeiger is told that “the why” does not matter. That is probably true. And yet, Tolstoy’s oft-repeated lines, “All happy families resemble one another; every unhappy family is unhappy in its own way,” perhaps could also apply to authoritarian governments. While they share common aspects, they are, each of them, particular to their time and to the culture and history from which they arise.’

Read the review here.

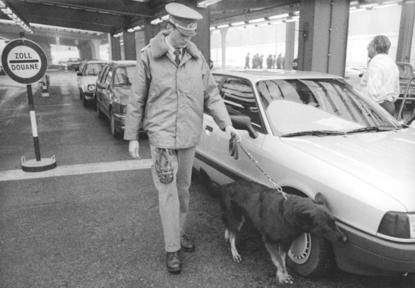

The history of the German Democratic Republic or GDR or East Germany is outside Germany largely forgotten or treated as a footnote or used to belittle an enemy (‘Stasi’ has become a swear word), but indeed East Germany treated fascism first and foremost as a bourgeois invention – like the Soviet Union for that matter – for which the other Germany was to blame, something that the philosopher Susan Neiman in her recent book on Germany, the US and reparations refutes. The most popular movies about the GDR (“Good Bye Lenin!” and “The Lives of Others”) share a benign nostalgia also called ostalgia, the GDR as a benign dictatorship. And compared with the Third Reich it was fairly benign, fairly, and needless to say the real victims would disagree with this statement.

One more quote:

‘“The self is a vessel that when turned upside down will empty itself of meaning,” Zeiger thinks. “It will grasp, cling to itself, turn in on itself, witness itself, go insane in that way.”’

The self is a vessel that will empty itself of meaning even without being turned upside down.