On socks, Nazis and absurdity – Regina Rini in TLS:

‘I discovered I was balling the same pair of socks twice. They were distinctive socks, the only pair with that checked fringe. And yet here I was balling them up again, just minutes after putting them into the finished pile. How? Had they teleported back to the fresh-from-the-dryer basket, magically unwinding en route? Was it a poltergeist? Enterprisingly tricksy cats? Or was I losing my mind?

The last, it turned out, though only in a minor key. I gradually realized what had happened: my memory of balling up those socks was not from minutes earlier. It was from 2 weeks back, the last time I did laundry, in the same location with the same clothes in the same pattern. My problem was that the weeks between sock-ballings were so utterly monotonous: always in the same place with the same objects in the same patterns. Without new experiential waypoints, my memory compressed across the weeks, smearing the edges of the now and the some-time-ago. It was as if I’d been standing there, mid-laundry-shuffle, for an unnoticed fortnight.

So much of daily life feels like that now, months into the pandemic, with travel restricted and public establishments shuttered. We seem to be living our lives in domestic spin cycles: the same places, the same objects, the same patterns.’

(…)

‘Covid has made us conscious. Conscious of our mortality, our monotony, the absurdity that our entire planet’s way of life can be disrupted by a wayward scrap of RNA. And perhaps that is why Camus really is the hero for these times. Because, for Camus, the ultimate opponent is not any god, but godlessness – the realization that our universe is unguided, unloved, and full of “unreasonable silence”. In that sense, folding socks really is more dramatic than fighting Nazis – it is monotony that makes us conscious of our inescapable existential struggle against the undefeatable enemy of meaninglessness.’

Read the article here.

This is a rather bizarre reading of Camus’ ‘The Myth of Sisyphus’.

It’s not the so much monotony that Camus is interested in when he writes about Sisyphus or Don Juan or the actor. Of course, repetition is key, the relentless seducer cannot avoid repetition, in a certain way an actor must repeat what he did last night, but only in a certain way, and above all repetition and monotony are not the same.

It’s no coincidence that Camus wrote about Don Juan and not about a man balling the same pair socks over and over.

If balling socks is more ‘dramatic’ than fighting Nazis – what a strange comparison – then we might as well conclude that being dead is more dramatic than being alive.

We might conclude that there is no difference between death and life. Camus knew this difference very well, actually his essay is an attempt to see the coldness of the absurdity without falling in the trap of suicidal thinking, His essay is an adventure, and although he has no interest in moralizing, he doesn’t deny the consequences of our deeds, also the moral consequences.

The utter lack of imagination, the inability to believe in your own fantasy is probably dramatic and tragic, but profound thinking is something else.

Fighting Nazis, balling socks, killing your husband or mopping the floor, what’s the difference? But that’s not at all what Camus taught us about absurdity.

The meaninglessness is real, yes, we attach meaning to our lives, to our suffering, to our joy sometimes et cetera. And meaning can escape us, our capacity to believe in the meaning we try to attach can let us down.

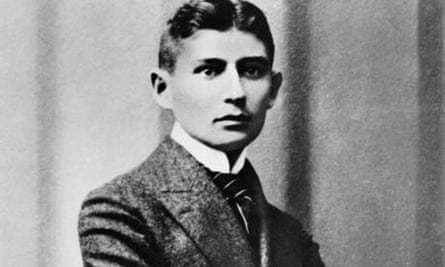

Camus ends his book with a meditation on Kafka, he talks about the greatness of artworks.

He asserts that Kafka denies God any moral greatness, evidence, goodness and cohesion, but despite all this Kafka, according to Camus, throws himself violently in the arms of God.

Kafka didn’t dedicate his life to the task of balling socks, but he would have been capable of doing it with such a grace and greatness that balling socks would have turned out to be a seductive endeavor.

What’s absent in this essay by Regina Rini is grace, desire, the capacity to recognize greatness.

To quote Milosz: ‘Flawed and aware of it Desiring greatness,/

Able to recognize greatness wherever it is, /

And yet not quite, only in part, clairvoyant,’

See also here.