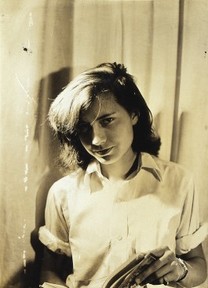

On freedom, secrets and bit of Žižek – Alex Clark in TLS:

‘The secret of writing successfully, advised Patricia Highsmith (1921–95) in her slim guide Plotting and Writing Suspense Fiction (1966), is nothing more than individuality – “call it personality” – and, since we are all individuals to begin with, this simply becomes a matter of finding a way to express one’s difference from the next person. “This is what I call the opening of the spirit”, Highsmith continued. “But it isn’t mystic. It is merely a kind of freedom – freedom organised.”’

(…)

‘Freedom and nakedness – or expression and exposure – are the twin poles that occupied Highsmith throughout her writing career, which is why her most memorable characters, from Guy Haines and Charles Bruno in Strangers on a Trainto Tom Ripley and Dickie Greenleaf, as well as Ray Garrett and his would-be assassin Ed Coleman in Those Who Walk Away, come in pairs; their progress through the novels is an agonized, slow-motion dance of attraction and repulsion. That this is an established method of the kind of claustrophobic psychological thrillers that now dominate bestseller lists, in which a protagonist is threatened by a chaotic, malevolent other who gradually reveals the fault lines in their prey’s superficially orderly life, is perhaps not entirely down to Highsmith; but it is difficult to think of them without her.’

(…)

‘Critically speaking, one tracks the life too closely at one’s peril, and risks what, in football commentary, for example, shades into chasing the game: retrofitting the action to the score. When Slavoj Žižek reviewed Wilson’s biography for the London Review of Books in 2003, he suggested that the idea of understanding the context of Highsmith’s life in order to understand her work was about-face; rather, it is that her work enables us to understand the context of her life and, what allowed her, in Žižek’s words, to survive it and to preserve her sanity. (It was a cursory review, to be truthful, analysis of the biography making way for such grand statements as “For me, the name ‘Patricia Highsmith’ designates a sacred territory: she is the One whose place among writers is that which Spinoza held for Gilles Deleuze (a ‘Christ among philosophers’)”.)’

(…)

‘That sense of separation from another, and from the materiality of the world, is what gives Highsmith’s work its emotional depth; it is why we can feel sympathy even for the loathsome Charles Bruno, also given to spells of faintness, as he embarks on the enterprise of murder in order to bond Guy to him (there might be no better evocation of the fantasy of inflicting mortal violence than the sequence in which he tracks Guy’s wife through a fairground and by a rowboat in order to strangle her in the bushes; it is a dream of pure desperation and domination, from start to finish). The world’s materiality is, of course, vital – nowhere more so than in Tom Ripley, whose class anxiety is stamped throughout the five books in which he makes his way from interloper to impostor in wealthy, artistic European society. (The Ripley novels, for obvious reasons of milieu, not to mention an occasional consonance of style, often bring F. Scott Fitzgerald to mind; it was delightful to discover that, in 2010, the magazine Fiction Circus held a séance for Fitzgerald, in which the writer purportedly said that he wished he had written The Talented Mr Ripley.)

Highsmith’s physical world is partly one of transitional spaces – bars, hotels, ticket offices, trains – and partly one of objects that can’t seem to be got rid of (the rings Ripley steals from Dickie Greenleaf; Guy Haines’s pearl-handled revolver). The notion of continual movement simultaneously represents escape to and flight from, the opportunity of a new beginning somewhere else, the possibility of one’s problems and one’s predators following on.

Going back through Highsmith’s oeuvre, one is, mind you, left feeling that it is best to be tormented somewhere nice; you might not just get thrown off a boat but, as in the small-town America of Deep Water, also end up at the foot of a quarry, having been bored to boot in the meantime. Better to be sipping cappuccino in Italy than seething in marital disharmony waiting for your steak to get cooked.’

Read the review here.

Most certainly, continuous movement, escape to and flee from. That’s life. Somewhere it ends. Quintessential is to be conscious about, there’s always an escape to and a flee from. That's what people call inspiration.

And don’t wait for your steak to get cooked, yes in a restaurant, but half an hour is max.