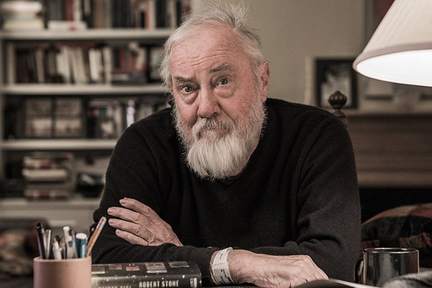

On the writer and his quarrels - Thomas Powers in LRB:

“There it is: the twilight childhood of Robert Stone, who wrote eight substantial novels about natural depravity in a fallen world. The strange thing, as described by Madison Smartt Bell in his new biography of Stone, is the writer’s acceptance of the cards life had dealt him. His mother was ten kinds of crazy, but she cared for him before all others, made him feel loved and taught him to read; the Marist Brothers kicked him out of St Ann’s Academy, but they schooled him in ‘making the best of a hard world’ and taught him to read poetry in Latin. The Catholic world had been the one solid thing in Stone’s childhood. When that went, he could be said to come from nowhere.

On the loose at eighteen with no high school degree, Stone joined the navy to see the world, and he did. Back on the city streets three years later he got a writing job on the Daily News and began college at New York University, where he encountered two people who changed his life: Janice Burr, who liked him more the more she knew him, and M.L.‘Mack’ Rosenthal, a poet, critic and teacher of narrative writing, which Stone knew was what he wanted to do. Rosenthal twice urged Stone to seek a Stegner Fellowship in fiction at Stanford. The second time, at a chance encounter in Washington Square Park after Stone had dropped out of NYU, Mack told him that his lack of a degree would not matter – a Stegner did not require one. Stone applied and Stanford said yes. In the summer of 1962 he headed to California with Janice, now his wife, leaving nowhere behind and entering the mainstream of American life.

Bell’s biography is an unusual book, written by a ‘close friend’ (in Bell’s words) and divided into eight parts, named for Stone’s eight novels. Each part relates the genesis, the false starts, the tortured progress, the ordeal of finishing, and the critical and commercial fate of the novels as they appeared. Bell’s approach may sound mechanical but it suits the life of a writer who seems to have done very little – other than write, think about writing, teach writing and spend his off-hours under the influence of mind-altering chemicals. Bell cites their names, doses and frequency of use on dozens of pages. His index includes separate listings for alcohol, cocaine, LSD, marijuana, Peyote, quaaludes, Ritalin and habit-forming prescription drugs. Alcohol was a problem until the end, but tobacco Stone managed to give up in his mid-forties, prompted by a cancer scare. His wife said it was the hardest thing he’d ever done. Still, it got him in the end, through emphysema.”

(…)

“He [Stone] had already moved back to New York to finish and publish A Hall of Mirrors, which appeared on his thirtieth birthday, 21 August 1967, and won a Houghton-Mifflin Literary Fellowship. The book’s reception was a first-time writer’s dream: glowing reviews in the best places, a contract for a British edition, solid sales and a quick agreement for a second novel. A Hall of Mirrors had literary energy and a strong narrative pull, but the quality that set the book apart was not strictly literary. Stone had a prescient sense of something dead ahead in the American road. He hadn’t figured it out in a bookish way, but simply smelled it on the wind, like a wolf in winter catching the scent of something injured and vulnerable. The novel’s main character is a heavy-drinking radio personality called Rheinhardt who lands a job with a New Orleans station: ‘WUSA – The Voice of an American’s America – The Truth Shall Make You Free.’ It is here that Stone’s genius takes hold. Rheinhardt’s hammering broadcast style and message prefigure the formula embraced by Rush Limbaugh two decades later: ranting, fact-free hostility to government, gays, welfare cheats, communists at home and abroad, American rich kids who don’t love the country but won’t leave it. The novel, like Rheinhardt’s mighty river of invective and resentment, lurches towards apocalypse. The owner of WUSA is a tycoon of sinister purpose who hopes to use the airwaves and Rheinhardt’s rants to trigger an anti-black bloodbath. What Stone imagined was radio’s potential to spark the explosion of hatreds that often seems just around the corner in American political life. ‘I put every single thing I thought I knew into it,’ Stone said much later. ‘I had taken America as my subject, and all my quarrels with America went into it.’”

(…)

‘(…) 1971, with the movie dead and gone, Stone turned full-time to the effort of a second novel. He had an editor but nothing to show, not even a clear idea. In London, where Stone and Janice and their two children were living at the time, ‘all anybody could talk about’ was the war in Vietnam. The next step was the obvious one: ‘I realised if I wanted to be a “definer” of the American condition, I would have to go to Vietnam.’ To go he needed credentials, an official letter to confirm that he was a real writer with an editor waiting for copy. A start-up London paper called Ink provided this, and Stone bought cheap air tickets to Kuala Lumpur, Bangkok and Saigon. Right up until the moment of departure he shrank from going, fearing he would be killed, but he was on the plane when it landed in Saigon on 25 May. It was a Tuesday, in the seventh year of the full-scale American effort to prosecute the war.

Vietnam in 1971 was filled with writers who had gone to see the war. Many had been there for years and new ones arrived all the time, but few carried away as deep an impression of events as Stone, and none, I feel certain, got it more quickly. ‘How long were you in Vietnam?’ he was asked in 1975 by William Heath, who later edited Conversations with Robert Stone (2016). Heath’s flat question was impossible to ignore. ‘Just a couple of months, something under three months,’ Stone said, ‘which is, I admit, not very long, but all I can tell you is every day was different.’”

(…)

“But a deeper, in some ways even scarier impression was left by the Saigon underworld with its war-wounded and homeless street kids, its teenage prostitutes and thieves, and its ‘skag-bars’ selling heroin in multiple user-friendly forms – as a booster in cans of beer, as an additive in cigarettes, or as a powder for snorting or injection. War was the business of the day – ducking it, waging it, arguing about it – but next to war came drugs. It seemed to Stone that among the writers he saw, a ragged mix of big names and the unknown, everybody was a user or a dealer. On Perry Lane, drugs had been a form of recreation; in Saigon their sale and consumption was of a different order of magnitude.

Stone’s dozen days in Saigon were all passed in the shadow of the war. Everybody was in it, somehow, and talked about it non-stop, but the talk never went anywhere. It ran into the war and came to a full stop. The war refused to be won, or lost, or understood. In the street one day Stone dropped ten piasters into the hat of a man without legs. The man smiled. ‘Who knows why he’s smiling,’ Stone wrote when he got back to London. ‘The legless man is one of the many blown-up people one sees about the city.’ Full stop.

Over dinner at night, or in the street, the writers and reporters told one another their stories: a tiger killed in a free-fire zone by napalm, elephants on the Ho Chi Minh trail shot to pieces by Americans in helicopters, a tax office in downtown Saigon blown up yesterday by a bomb, six people killed. It’s not clear who did it – maybe an angry citizen, maybe the National Liberation Front. Tales of this kind ended with a catchphrase Stone soon picked up. The pattern is always the same. The tale offers much detail, ends with its point of shock or horror, followed by a brief pause, then – ‘There it is.’ It is evident Stone heard this a hundred times, maybe a thousand – ‘There it is.’

He struggled for the right translation of ‘it’. Sometimes, he felt, the speaker meant ‘the Whole Expedition ... the War ... this shit’. A Marine he knew called it ‘Captain Gray Rat’. Stone himself thought of it as ‘the war’s infernal, antic spirit’. These attempts all get close, but they all miss the finality of ‘There it is’ – recognition that a limit has been reached, a thing like a wall, the point where human reason shrugs. I think ‘it’ is better translated as ‘the thing about which nothing can be done’.”

(…)

“Dog Soldiers was published in 1974, at what proved to be just the right minute, when the US was thoroughly sick of arguing about the war but was beginning to notice what it had done to us. Some reviewers gave Stone rough handling for being a hippie, but most noted the sober artistry of the book and the force of its message. For the actual writing Stone got favourable mention in sentences that included the names of Mailer, Chandler, Faulkner, Baudelaire and even Chaucer. The reviewer for the Washington Postcalled it ‘the most important novel of the year’. The book sold well and won a National Book Award, which is one of the few triumphs the American literary world never forgets.”

(…)

“In a fallen world what happens is a matter of chance, and chance doesn’t care what happens. There it is – the thing about which nothing can be done.”

Read the review here.

I’m not sure if I’m going to read Stone, but the wall, the point where human reason shrugs reminded me of a poem by Milosz. I could not find that particular poem in translation, but I did the first line of ‘Account’, another poem by Milosz:

‘The history of my stupidity would fill many volumes.’

Which is another way say that chance doesn’t care what happens.

From there the acceptance of the cards life had dealt you is just a tiny step.