On a non-existing novel – Michael Hofmann in TLS:

‘This degree of – literally, etymologically – prescriptiveness is surely intolerable to authentic fiction; in Tóibín’s hands the form is reduced to the status of copying. Both books to me are like biopics, a slightly vulgar, slightly unattributable, cod replaying of celebrated or distinguished lives. Call them bionovs.

The Master (2004) came in somewhere at the bottom end of expectations, but, so long as one could tolerate the weirdly matey – or astoundingly disrespectful – “Henry this, Henry that”, it passed. It was written plainly, sometimes in a kind of binary code so impoverished that, had there been one more “Henry watched” or “Henry smiled”, it would have finished me. The project is suitably unheroic too: something like Middle-Aged Author Mulls Over Life and Prospects and Moves House. It took a manageable chunk from James’s life – five years – and showed us a man in solitude, industrious, introverted, mostly distant from men and women alike, and written in empty, memorable, rather Whistler-ish scenes: we see “Henry” standing under a lamp post in the rain; turning over a dead woman’s papers; unexpectedly running into an acquaintance in an antique shop. The locations keep their integrity and ensure some separation – Paris, London, Rye, Newport, Venice, Rome. No doubt the “peppering” of actual James phrases helps. Dialogue is kept to a minimum, fortunately so, with the Master sounding to my ear suspiciously like a certain Gentleman’s Gentleman: “As you know, I do my best to please you”.’

(…)

‘Tóibín has a dozen, or even a score, of people to push through sixty years; that makes perhaps a thousand man-years, or Mann-years, and he can’t afford to stop too many times. And so the poor words come out for them to speak. Like little soundbites, little what-might-have-been-said-by-you-or-me-in-similar-circumstances samples. Scenelets. Description intolerably bland: “In the confusion created by the war”, or “her clothes understated and expensive”. And if not that, then mystifyingly self-annulling: “The young children enjoyed having friends with whom they could roam under the careful eye of a governess”. I bet they did. Or there is Katja Pringsheim, the daughter and granddaughter of feminists, who “had a way of finding the very centre of an argument and following a logic that she established from the beginning” – hard enough already, one would have thought (it sounds like God planting the fossils), but in the next paragraph, one learns, she “applied her mind to small matters, such as whether there should be art books on the low table in the main sitting room”.

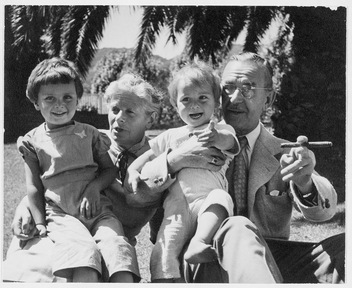

And so we are hustled through the death of father; mother’s move from Lübeck to Munich; the first books of Thomas and his older brother Heinrich; the courting of Katja; marriage to same; children, one through six, and their interrelationships and little burgeoning personalities; the First World War and the embarrassing nationalism of the slow-to-come – like many of his books – Betrachtungen eines Unpolitischen (Reflections of a Non-politcal Man) of 1918; the Twenties, with their softening, now democratic politics, family life, shrill children, Magic Mountain, Nobel prize; fortuitous exile, Switzerland, Sanary-sur-Mer, Princeton, Santa Monica, international distinction; the deaths, en route, of two Mann sisters, the old Brazilian dowager mother, a son-in-law, the suicide of Klaus.’

(…)

‘The Magician isn’t just a bad book, or a misconceived book, or a book that should never have been written: it is in some sense a book that doesn’t exist. Crap hat, no rabbit.’

Read the review here.

The least one could say is that Michael Hofmann (I must have mentioned that I read his poetry in Dutch translation when I was 18 or so - I remember the poem ‘Author, Author’ that begins with the line ‘Imagine Flaubert with a wife and four children,…) knows what style is, he knows how to make you laugh, perhaps Schadenfreude plays a small role – who is completely beyond schadenfreude – but I have nothing against Tóibín, au contraire.

A woman told me once that she had a reluctant lover who used to text after sex: ‘Because of our last rendezvous the rest of the year is bearable.’

With sentences like this, ‘Dialogue is kept to a minimum, fortunately so, with the Master sounding to my ear suspiciously like a certain Gentleman’s Gentleman: “As you know, I do my best to please you”’, the rest of the day is certainly bearable.

I never read ‘The Master’ but now I’ll give it a try. I happen to like things and beings that come in at the bottom end of expectations.