On Rawls – Andrius Gališanka in TLS:

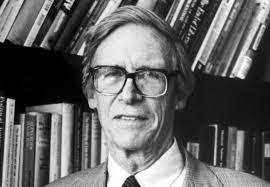

‘Those seeking to understand liberal debates about the justice of contemporary societies will in one way or another gravitate to the writings of the American political philosopher John Rawls (1921–2002). Rawls’s influence has been so vast that he is often described as having revived analytic political philosophy in the mid-twentieth century. Having pronounced political philosophy “dead” in 1956, Peter Laslett introduced Rawls’s article in his edited volume of 1967 by declaring political philosophy “alive again”. President Clinton, conferring on Rawls the National Humanities Medal in 1999, similarly claimed that, “[a]lmost singlehandedly, John Rawls revived the disciplines of political and ethical philosophy”. These claims are exaggerated, but they nonetheless gesture towards the novelty of Rawls’s arguments. In his most famous work, A Theory of Justice (1971), the fiftieth anniversary of which is marked this year, Rawls aimed to outline a vision of justice which reasonable persons could come to share. In retrospect, perhaps the most striking fact about that book is that Rawls did not seriously doubt the possibility of such a shared vision.’

(…)

‘Rawls focused on inter-personal relationships within it and with God. As he put it, proper ethics “is the relating of person to person and finally to God”. It was clear to Rawls that proper relationships required equality among the members of that community (although he had not yet specified what this equality required in practice). Second, Rawls believed that the task of philosophy is analysis of experience – religious or otherwise – and a construction of a conceptual framework that could explain this experience. This position assumed that human beings could make a judgment about a particular case and yet not be able to formulate the reasons behind that judgment – an insight that would stay with Rawls until the end of his life. Philosophy was to play a clarifying role.’

(…)

‘A Theory of Justice was published in 1971, but Rawls had worked on its ideas from the early 1950s, when his focus turned to the virtue of justice. Though only one of the virtues, justice treated “especially important” interests of persons, such as life and liberty. This sufficed for Rawls to describe justice as “the first virtue” of social institutions in that it trumped others: laws and institutions had to be reformed if they were unjust, no matter how virtuous they were in other respects (efficient, generous, humane, say).’

(…)

‘One of the most important conceptual innovations of A Theory of Justice was its focus not on the justice of individual acts but on the justice of the web of social institutions of a society – political institutions such as the US Congress, economic institutions such as private property, and social institutions such as the family. When taken together, these institutions formed what Rawls called the “basic structure” of a society. This emphasis on the basic structure arose as Rawls studied Wittgenstein’s ideas and especially his concepts of “practice” and a “form of life”. Rawls thought philosophy should study practices so ingrained in our way of life that they shape the kinds of persons we strive to be. The effects of the basic structure are thus “profound and present from the start”. Moreover, our initial positions in this basic structure “cannot possibly be justified by an appeal to the notions of merit or desert”. The initial inequalities – should they be allowed to persist in some form – have to be justified in some other way.

Rawls argued that the goal of justice is not to correct these initial inequalities (as “luck egalitarians” would have it), but to create a society in which every person is guaranteed equal political rights and in which social and economic inequalities are arranged so that the least advantaged persons can still lead the best possible life. He called this conception “justice as fairness”.’

(…)

‘But how could they be? Rawls’s simplest answer – one that mirrored social contract arguments – was that even the least advantaged persons would prefer economic inequality to a more equal society in which they personally fared less well than in the more unequal one, in terms of social and economic status. More importantly perhaps for the relational conception of equality, Rawls thought that by choosing a society that arranges inequalities “for reciprocal advantage”, its participants “express their respect for one another in the very constitution of their society”. What is at stake in inequality is respect for others, not merely the amount of primary goods each of us can receive.’

(…)

‘In comparison to his later work, Rawls in A Theory of Justice did not seriously doubt that political philosophy could reveal a shared vision of justice acceptable to all reasonable persons. He was open to the possibility that his own vision of justice might fail to do so, but insisted that some conception of justice can come to be shared. Entertaining objections he saw stemming from ordinary language philosophy and Wittgensteinians that the uses of a term reveal at best a mere “family resemblance” of meanings but not one shared, underlying meaning, Rawls loosened the kind of agreement he expected to attain among reasonable persons. Within justice as fairness, for instance, some could prioritize freedom of speech while others might select freedom of movement as most important. While loose, this agreement still seemed sufficiently important and stable for Rawls.’

(…)

‘In Political Liberalism, Rawls retained his earlier belief that political discussions should be informed by a shared conception of justice. In a new vocabulary, he now argued that we should decide the main political questions in terms of “public reason”, or society’s shared and public “way of formulating its plans, of putting its ends in an order of priority and of making its decisions accordingly”. Reasonable persons were still expected to agree on public reason, but this public reason stemmed from what Rawls called an “overlapping consensus” of various “comprehensive doctrines”, or doctrines that explained what is of value in life in general. Each comprehensive doctrine would endorse the same ideal, but from its own internal point of view. For example, John Stuart Mill’s liberalism might endorse freedom of speech due to its emphasis on individuality and self-exploration, while a libertarian might also see in it the justice of restricting the extent of government intervention. Supported by a variety of view points, this political doctrine of justice would be a “freestanding” doctrine: it would be compatible with, but independent of, the comprehensive doctrines that endorsed it. Thus, much like in Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s social contract, each citizen would still be governed by laws that stemmed from their own comprehensive reason.’

(…)

‘Nor were questions about the environment and its place in human life. Public reason now became essentially about political rights: freedom of speech, association, movement. This was a significant departure from the content of “justice as fairness” that Rawls had defended in A Theory of Justice.’

(…)

‘ However, since public reason does not require that different comprehensive doctrines agree in how they interpret these broad values, or how they weigh these values against one another, the broad terms arguably gloss over disagreement rather than create agreement.’

(…)

‘To arrive at the laws governing international society Rawls imagined a second original position in which liberal societies, having decided on their own visions of internal justice, would agree on a vision that would be palatable to them and to non-liberal “decent societies” that upheld human rights. If public reason for domestic societies was restricted to fundamental political freedoms, a global public reason would have to have an even more minimal content.’

Read the complete article here.

Still powerful questions: what kind of consensus can we expect in a society and how do we define fairness without just defending our own interests?

I happen to believe that humans have an innate tendency to abhor unfairness, but at the same time we can witness people busy overcoming this inhibition over and over again. We can witness it in ourselves.

Also, the questions what the actual difference is between the position that we should correct certain inequalities and the idea that we can have a society where the inequalities are arranged in such a way that the most disadvantaged person can have the best possible life is not clear.

What we see here is the possibility that people will compete for the status of most disadvantaged, not if we follow Rawls, but if we agree that reasonable people have the tendency from time to time to behave less reasonably.

And what’s the best possible life?

What if the most disadvantaged person has created these disadvantages himself? For example, a criminal who is on death row because he killed a salesclerk during a robbery that earned him ten dollars?

I would argue that this person also should have the best possible life within a system of justice.

Some people would argue that the best possible life for him is dying at the people’s earliest convenience.

And what about the people who claim that they are the most disadvantaged by definition? Between us and reason stands self-pity.