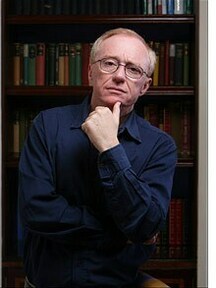

Last night I interviewed David Grossman in a theater in Amsterdam.

This anecdote, from a 2010 profile in The New Yorker by George Packer, is one of my favorite Grossman anecdotes:

‘After a translation of “See Under: Love” became a huge success in Italy, he began making frequent trips there to promote it. One night at dinner, on the eve of another departure, Uri, who was three years old, asked his father, “You have another boy in Italy?” It crushed Grossman, who imagined Uri’s state of mind: “Just think in what hell he must have been until he even formulated this question, because for him what could be a magnet that could attract me there and pull me away from him?” Whenever he went away, he recorded cassettes for his children, with stories and music, so that they had his voice while he was gone.’

Uri was killed in 2006 in the second Lebanon war.

‘Like all of Grossman’s major works, the new novel emerged from a feeling of alarm and threat, which he wanted to confront in order to avoid becoming its victim. At the time, Grossman’s middle child, Uri, was about to enter the armored regiment in which his oldest child, Jonathan, had just completed his service. The novel would allow Grossman to feel that he was accompanying Uri while Uri was away in the Army. Like Ora, he was engaging in magical thinking; though he knew it was childish, he felt as if writing the story could provide a kind of protection.

Grossman’s writing has a lyrical intensity that deeply connects the reader to his characters’ inner states, but he has also been a journalist throughout his career, and he grounds his fiction in facts. Before he began the novel for which he is best known—“See Under: Love” (1986), a dizzyingly inventive exploration of the Holocaust—so many books with swastikas on their covers defiled the small Jerusalem apartment where he and his wife, Michal, then lived that he moved his work to a studio. For “The Yellow Wind” (1988), a nonfiction investigation of the Israeli occupation of the West Bank, which made Grossman internationally famous, he spent nine weeks interviewing Palestinians. For six months in the nineties, he joined a Jerusalem detective squad several evenings a week to research “The Zigzag Kid” (1994); he then spent the better part of nine months with homeless teen-agers in order to write “Someone to Run With” (2000), the most popular of his novels among Israelis.

Grossman was on the Israel Trail for thirty days, waking at five-thirty and walking about ten miles a day, occasionally joined by Michal. He stayed in rented rooms in farming villages, where, after dark, he took notes on what he had seen: the trees and flowers of the Galilee, a group of Arab shepherd boys. The journey frightened him. He was an urban man, afraid of navigating his way home from afar. In Israel, being on your own in nature has its perils. An Israeli soldier had been kidnapped near the hiking trail recently and murdered. As it turned out, the only dangers that Grossman encountered were a pair of boars and a pack of wild dogs; he faced them down, calmly, and was left alone.

During the journey, Uri sent his father text messages, telling him that he was proud of him. Uri served mainly in the occupied territories, manning checkpoints and patrolling, and as Grossman progressed with the novel his son kept up with its characters in phone conversations and visits home on leave, asking, “What did you do to them this week?” Grossman usually shows ongoing work to Michal and a handful of friends, including his two peers among Israeli novelists, Amos Oz and A. B. Yehoshua. This time, the subject was too charged.

The novel was nearly complete when, in July, 2006, fighters of the Lebanese Shiite militia Hezbollah fired missiles across the Israeli border, killing three soldiers and kidnapping two others, who were mortally wounded. Grossman, like nearly all his countrymen, supported Israel’s right to defend itself. During the weeks that followed, which Israelis call the Second Lebanon War, he travelled north and read stories to children in bomb shelters. On August 10th, after a month of destruction, Grossman, Oz, and Yehoshua—major public figures in Israel—held a press conference in Tel Aviv. They urged the government to accept a ceasefire under consideration at the United Nations and the Lebanese offer of a negotiated peace. Grossman warned against the illusion that Hezbollah could be defeated by further Israeli incursions into Lebanon. “Hezbollah wants us to enter deeper and deeper into the Lebanese swamp,” Grossman said. “This disastrous scenario can be prevented right now.” Grossman didn’t mention that Uri, a staff sergeant, was a member of a tank crew in the thick of the fighting in southern Lebanon. His private concern was not the point of his statement.

The next night, a Friday, Uri called home, happy about the news of a possible ceasefire, promising his fourteen-year-old sister, Ruthi, that he would be there for the next Shabbat dinner. But Prime Minister Ehud Olmert widened the ground war over the weekend.

At 2:40 a.m. on Sunday, August 13th, the doorbell rang at the Grossman house. Over the intercom, a voice said, “From the town major’s office.” Michal had left the outside light on, in case of such a visit. As Grossman went to the door, he told himself, That’s it, our life is over.

Uri had been killed earlier on Saturday night, along with the rest of his crew, when their tank was hit by a Hezbollah missile in the Lebanese village of Hirbet K’seif. The war was in its final hours; a ceasefire went into effect on Monday. He was two weeks short of his twenty-first birthday and three months from the end of his Army service. He had planned on travelling around the world, then studying to be an actor.’

Read the complete profile here.

You have another boy in Italy?

A delightful combination of jealousy and humor.

Book promotion as a metaphor for another, a secret child, or the other way around.

Also, I recommend reading Grossman’s novel A Horse Walks into a Bar. If you don’t know where to start reading Grossman.